Risk management refers to:

“the practice of identifying potential risks in advance, analyzing them and taking precautionary steps to reduce/curb the risk.”

In rugby league the risks we are worried about are those that lead to the concession of points – the most basic of which is your opponent having the ball.

So how do we minimise opponent having the ball?

When in possession:

- Score within the 6 tackles

- Hold the ball for the full 6 tackles

- Force opponent to concede penalty/set restart

- Retain possession via forced drop out, 20/40 or 40/20

- Force opponent error on possession transition (eg difficult grubber/bomb)

- Avoid 7 tackle sets on possession transition

- Retain possession from kick-offs/drop outs

When not in possession:

- one on one steal

- intercept

- force offensive error eg knock on, tackle or pass over sideline

- force player into own in-goal

- prevent them scoring

- prevent forced drop out, 20/40 or 40/20

- prevent kick-off/drop out retain possession events

- win scrum against the feed

Nothing earth shattering here and I’m sure plenty of aww derr! comments but noting them all down is the process of risk management.

Now the fun part – what strategies can we apply?

For each element above a team needs to work out how they best manage it – this is where vast coaching resources are deployed – drone recording of training sessions, deploying defensive systems, tackling technique, attacking plays, yardage sets, last tackle options, opponent strengths/weaknesses etc all come in to play.

However given all this effort there are still aspects of the game that could be better managed.

This is where Dane Gagai can help us – because when a team has the ball they literally drop the ball on risk management.

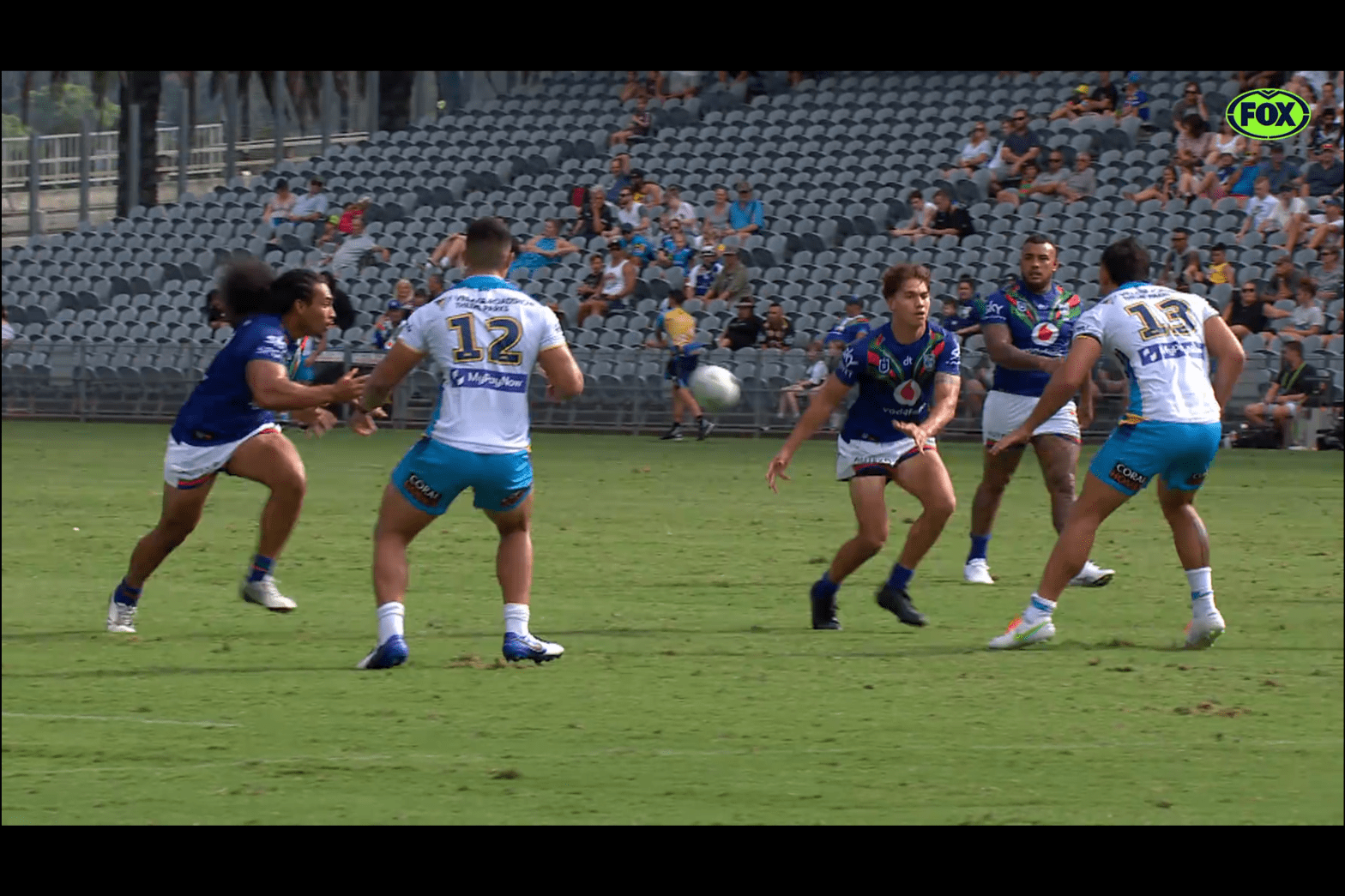

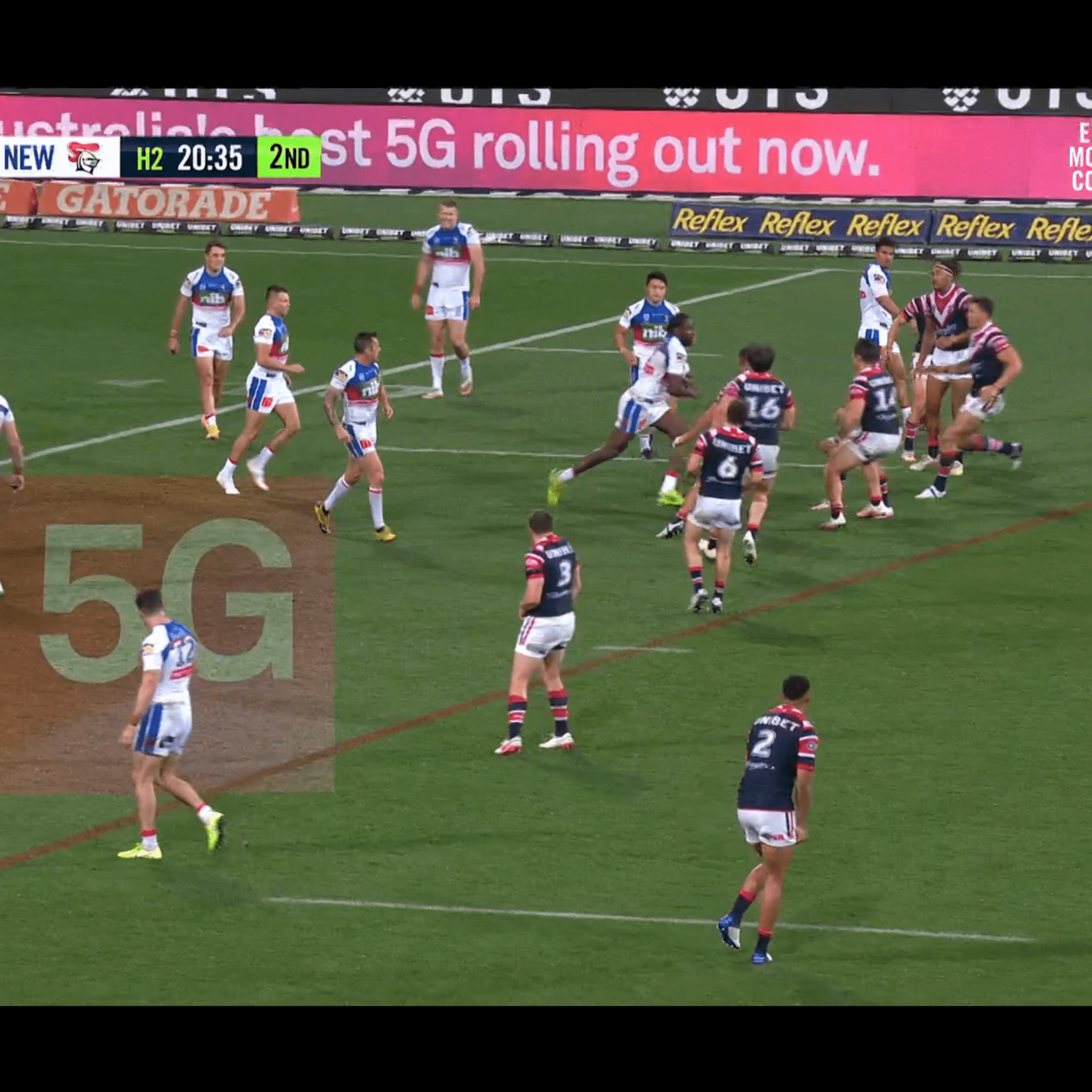

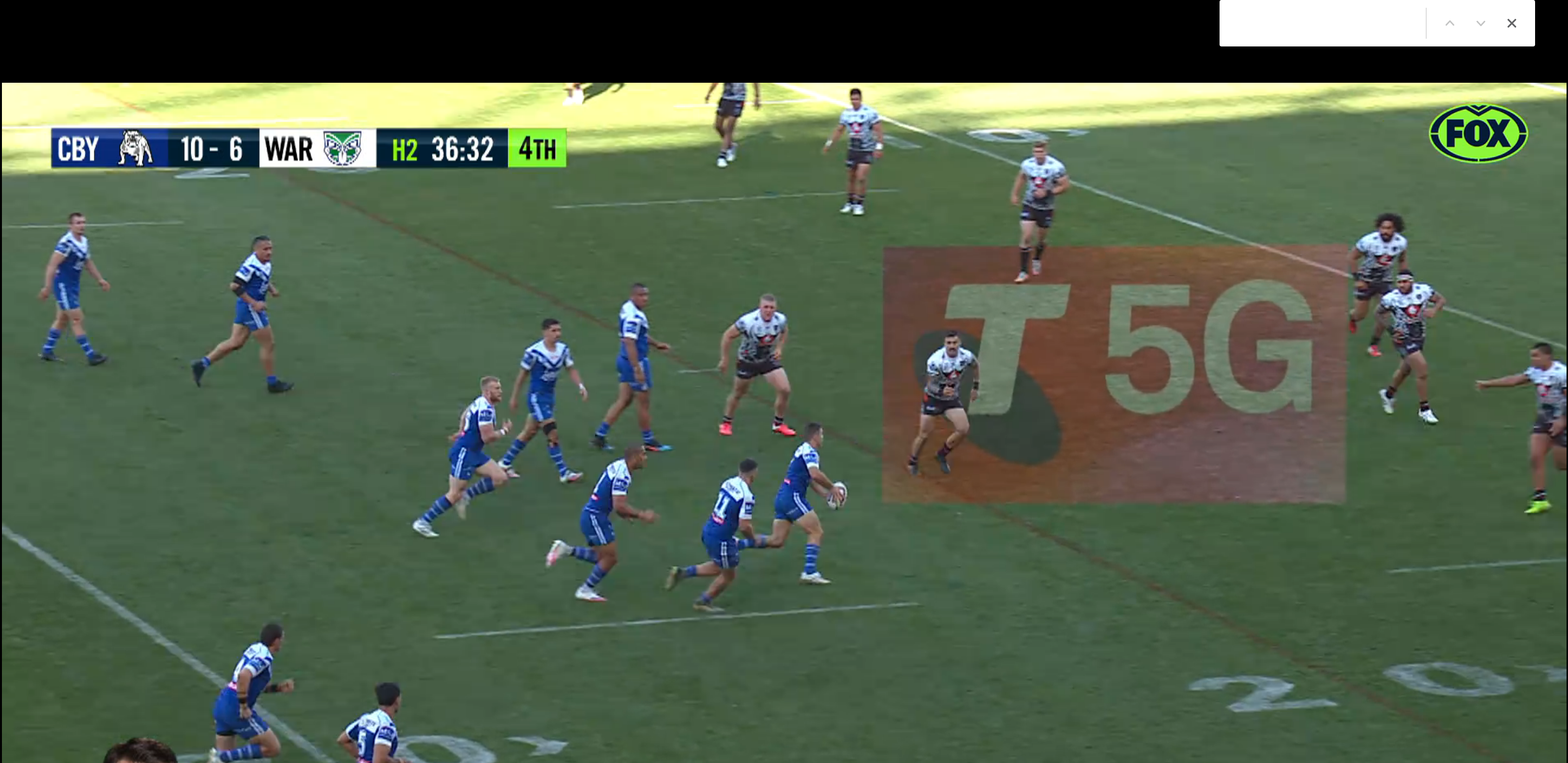

In the Dane Gagai example the Bulldogs are on the attack 10 metres out but have failed to manage the risk of an intercept.

As a risk manager I ask “why was no player behind the play in case this happened?” (there are other questions such as what can be done to prevent an intercept eg draw and pass execution etc but let’s focus on what we could do post intercept).

How difficult would it have been for the Bulldogs to have a player positioned behind the play “just in case”?

Normally the “just in case” manager is the fullback (and I will publish more posts on how to exploit this opportunity) but this doesn’t work if they are deployed in the attacking play – opening up a defensive hole in a team’s risk management to a fast change of possession – so it needs to be someone else.

A potential strategy

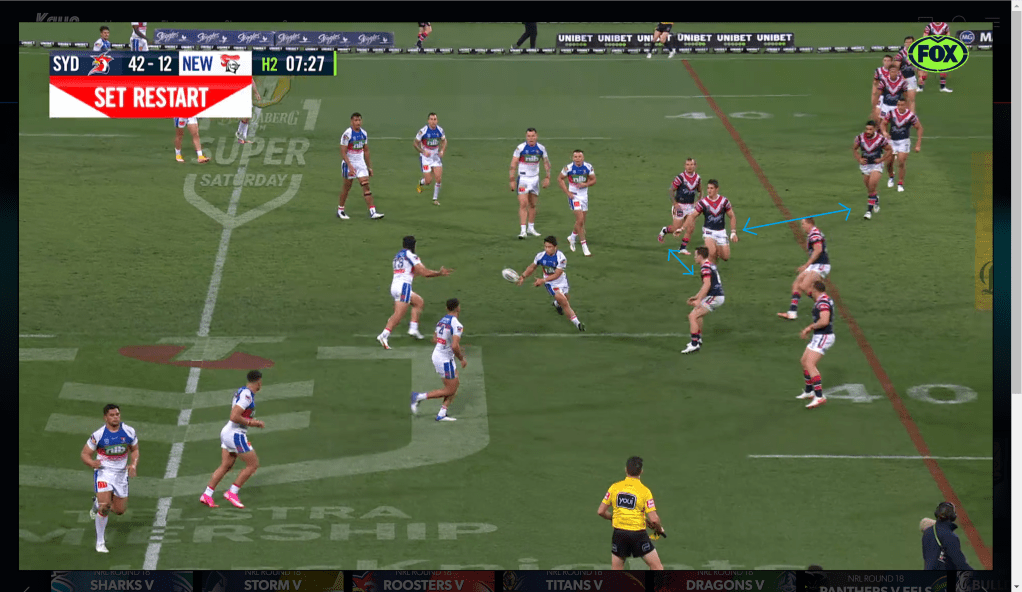

The player preferably shouldn’t be there at the start of the play to prevent signalling to the defence which side you are going to attack. An option could be for a far side attacker to rotate into a “defensive” position post shifting of the ball from dummy half.

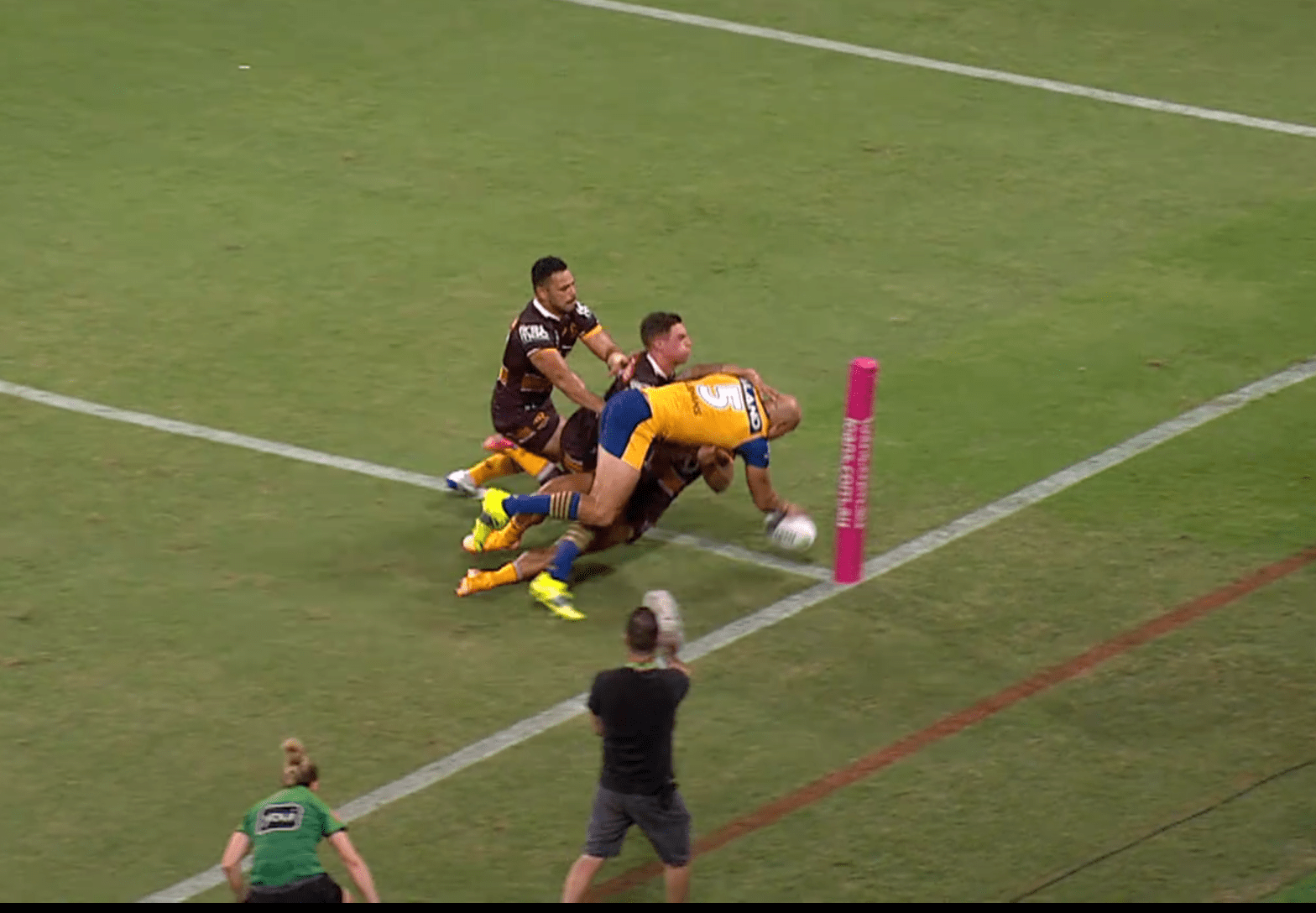

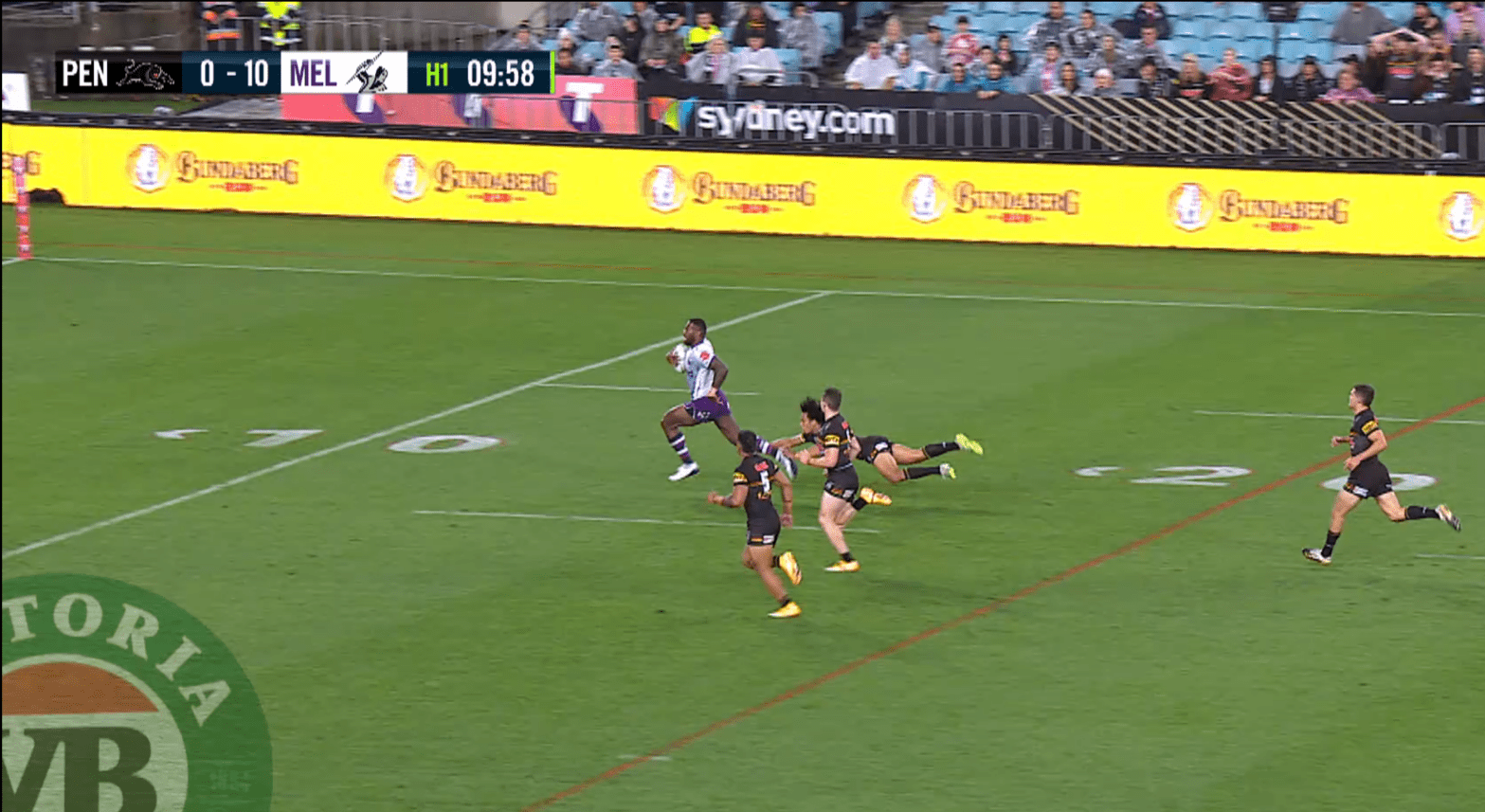

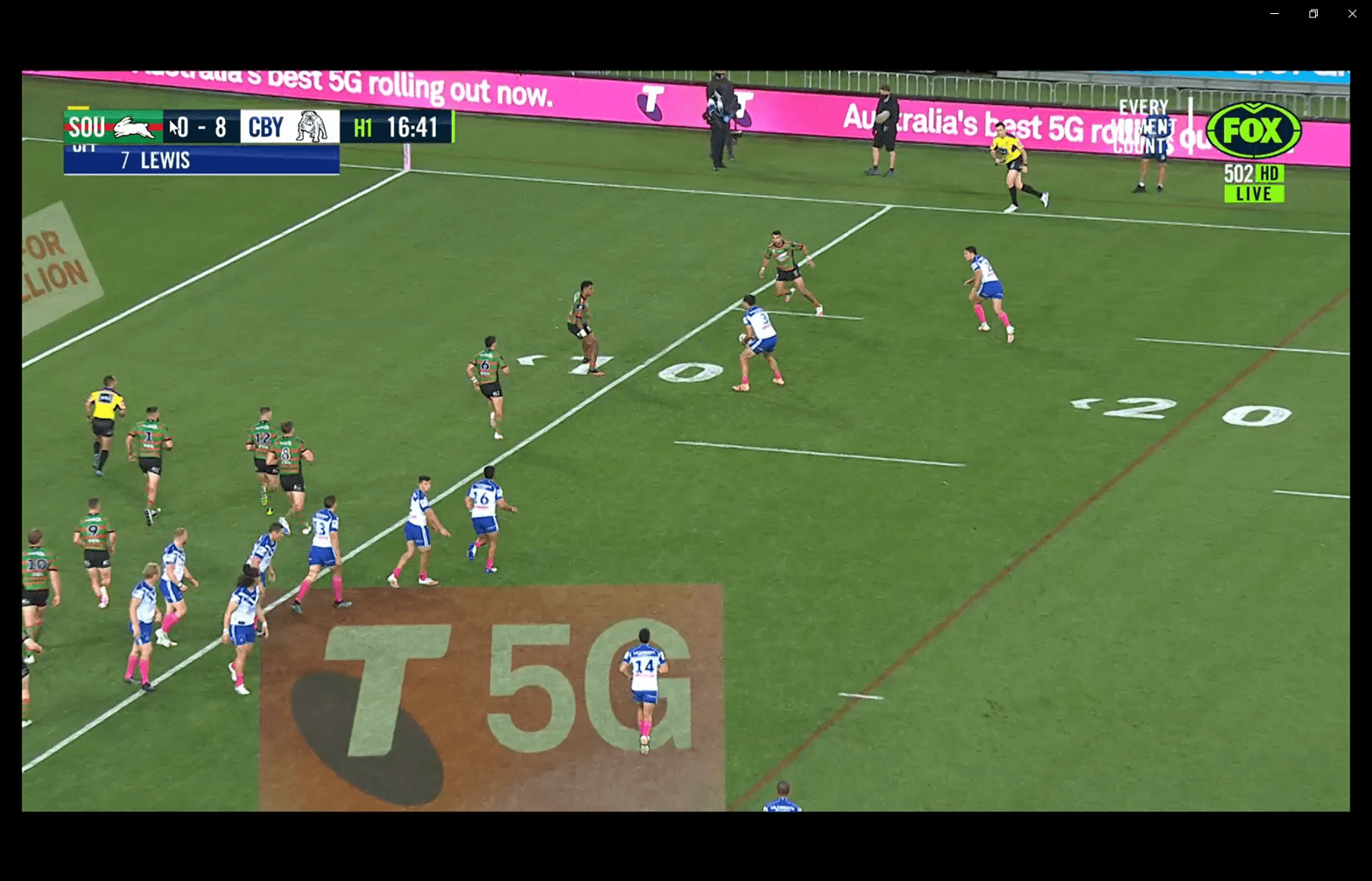

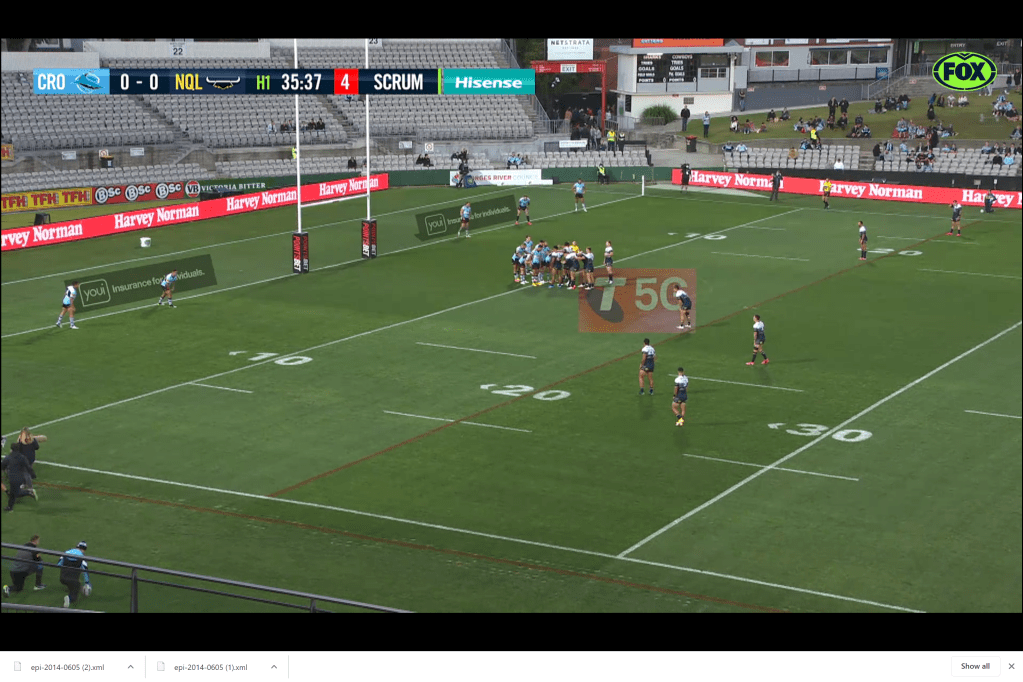

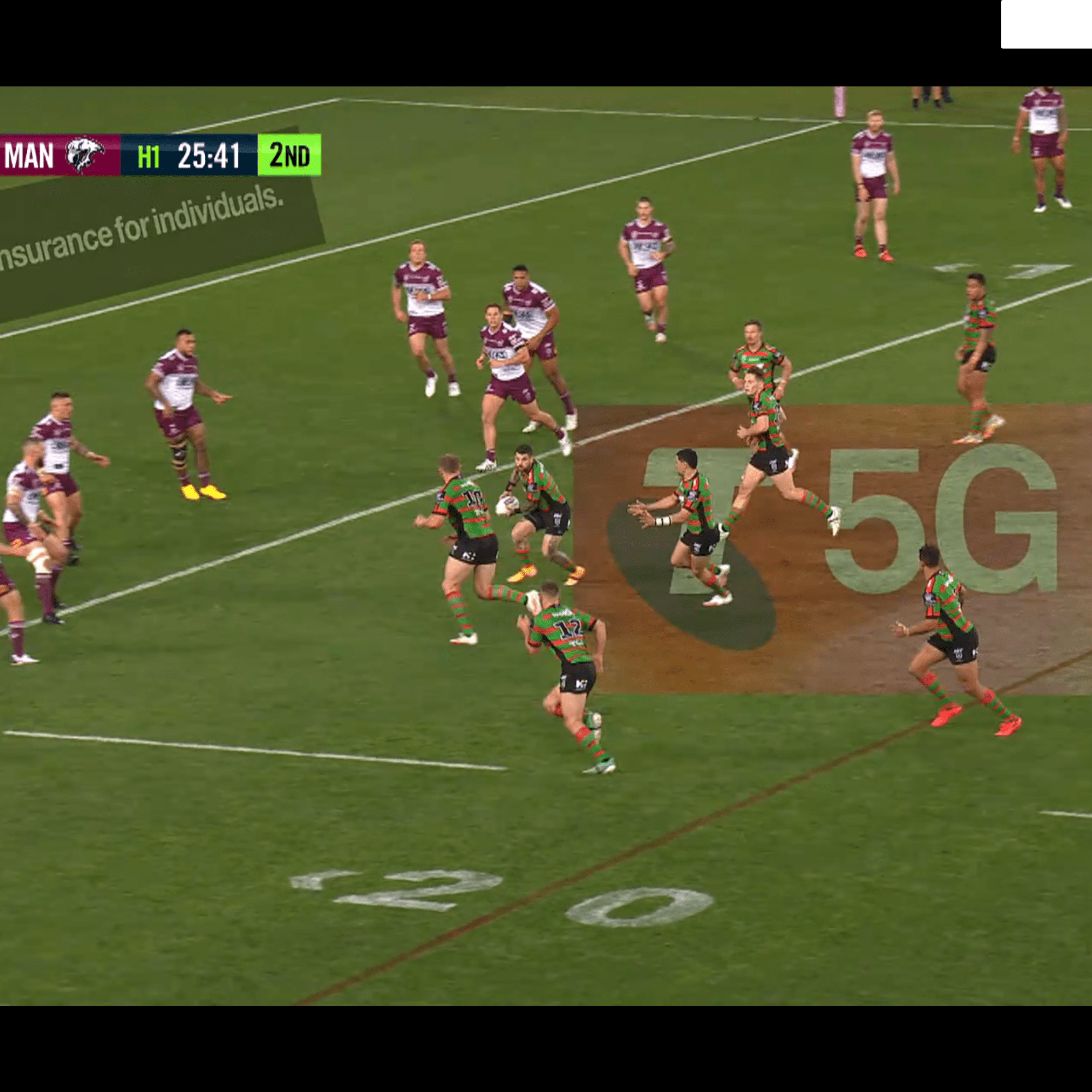

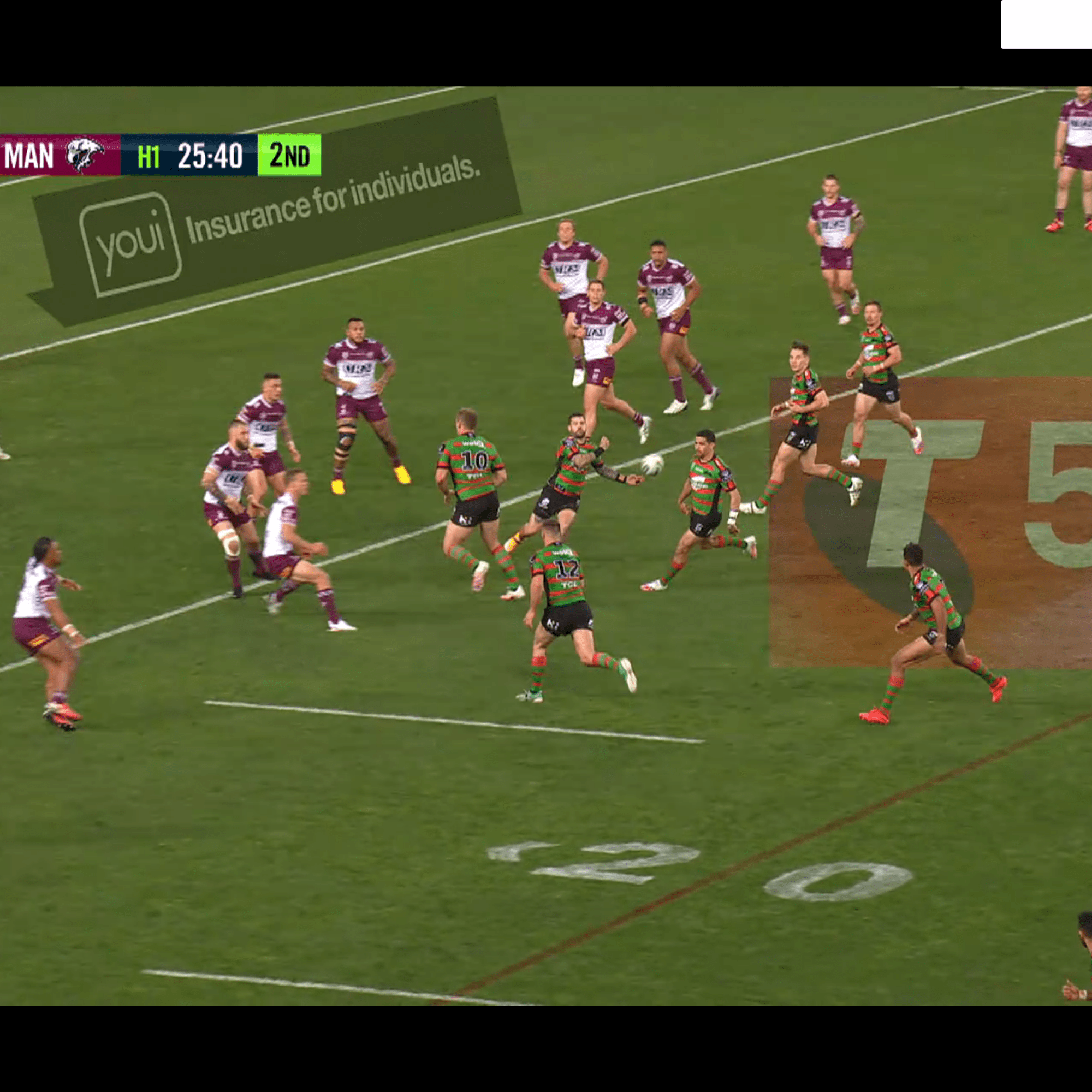

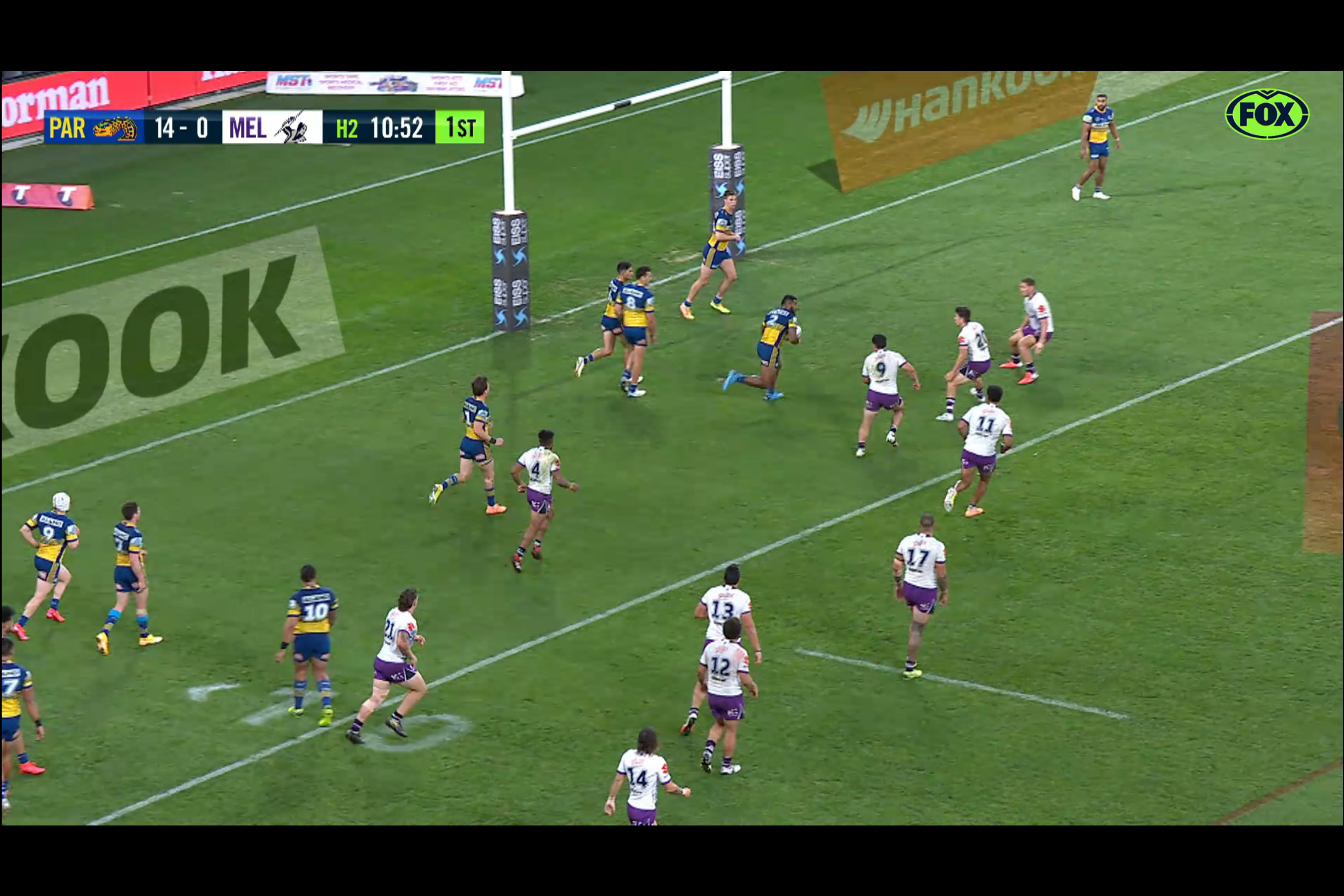

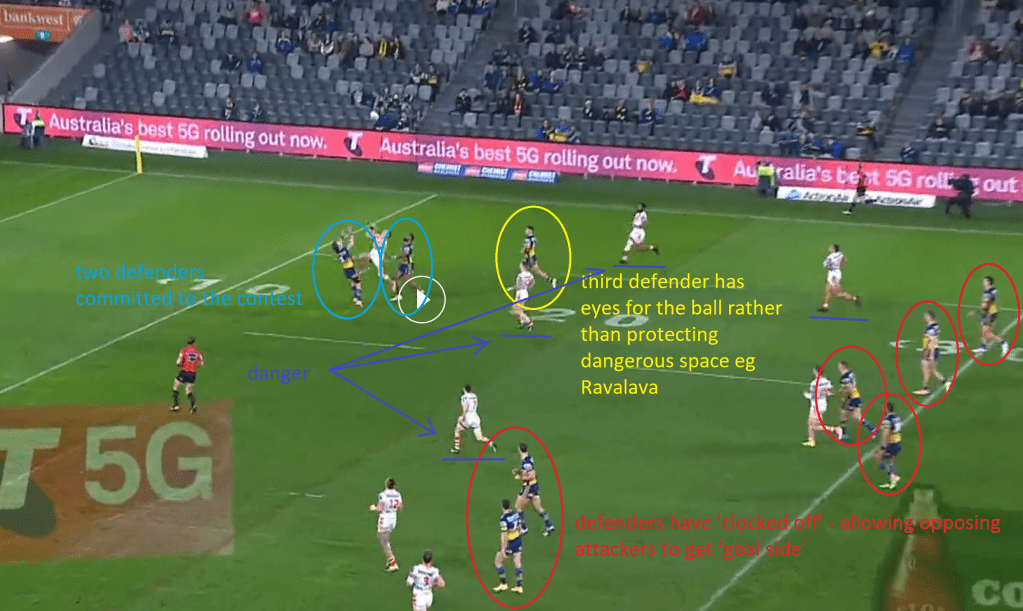

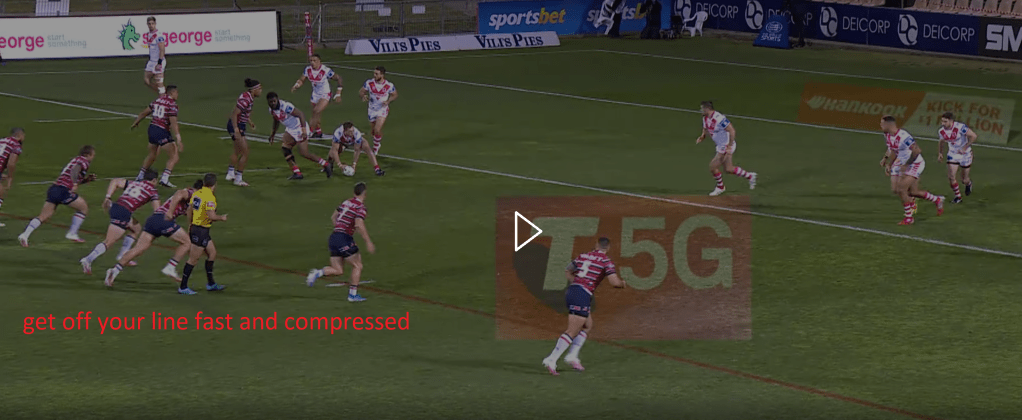

The sequence below is taken from the round 12 Souths vs St George game. In this case it’s not an intercept but a ‘trap and scrap’. Souths are attacking right – their fullback is on the left for shape but equally could have been involved in the play on the right.

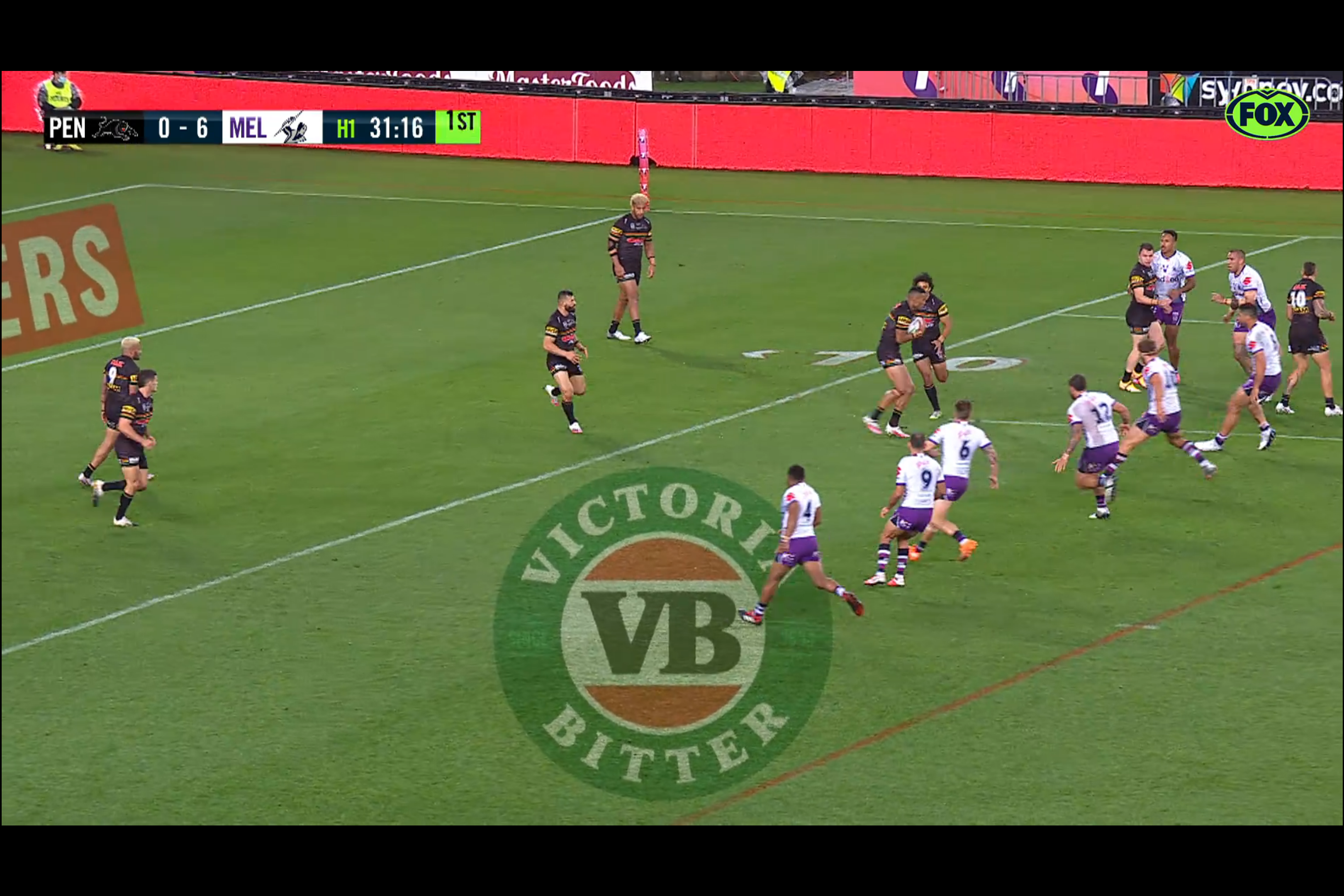

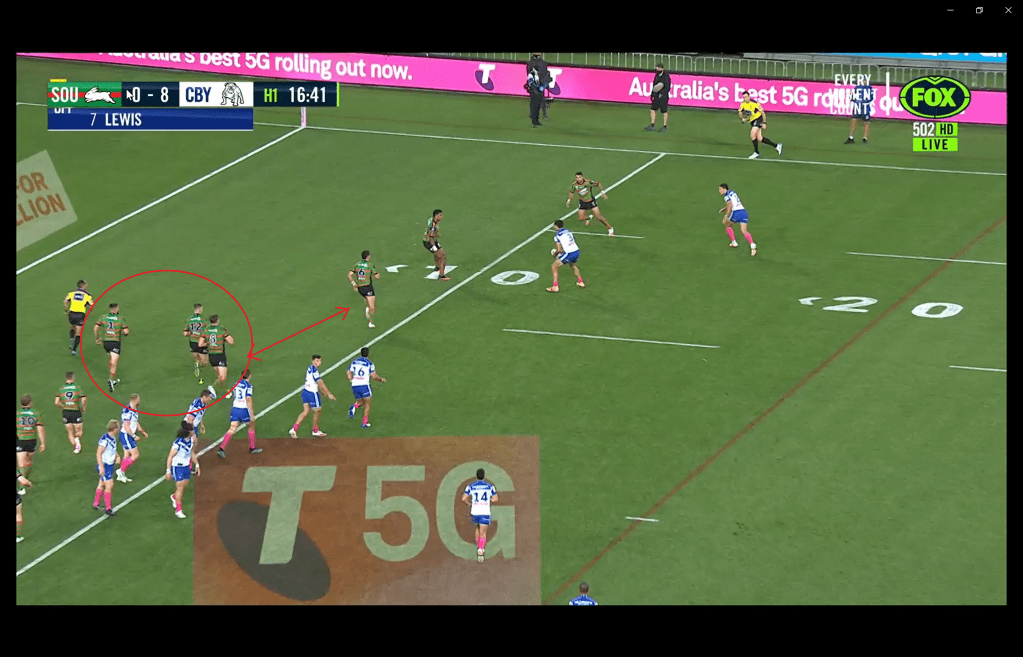

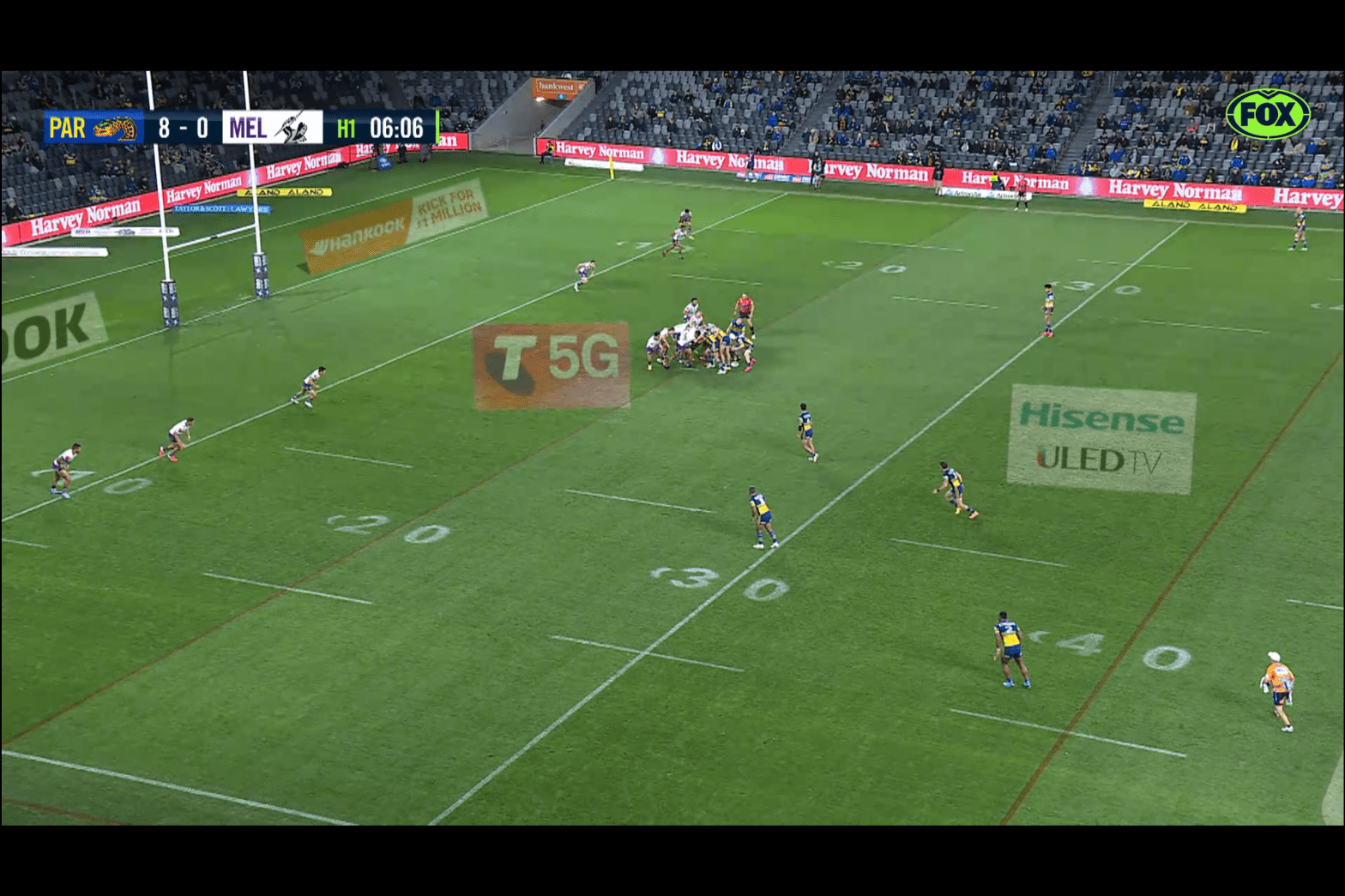

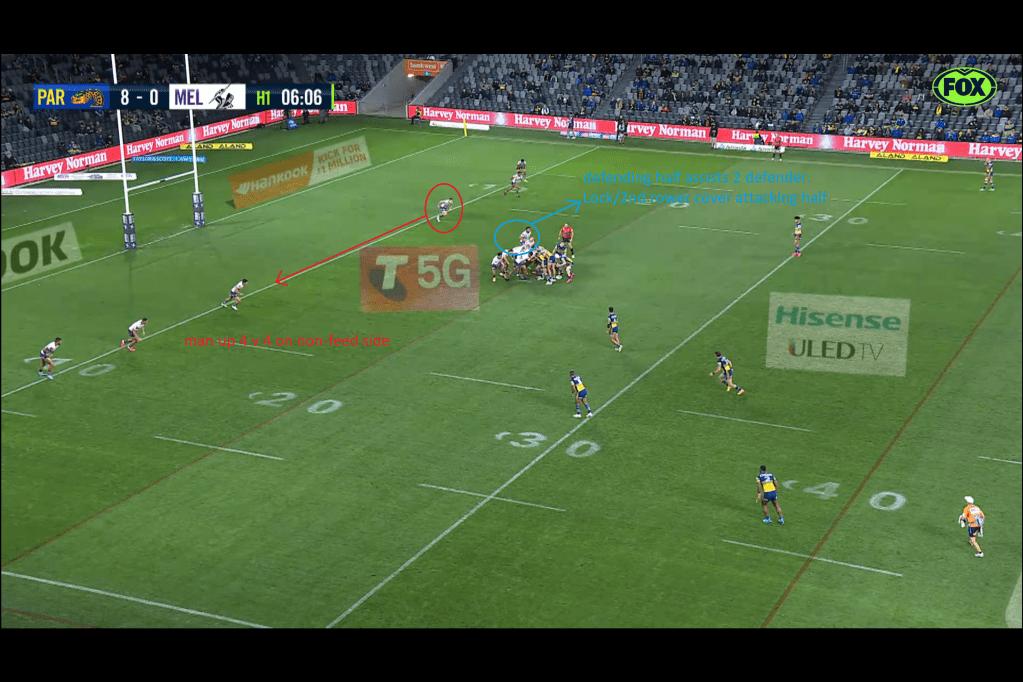

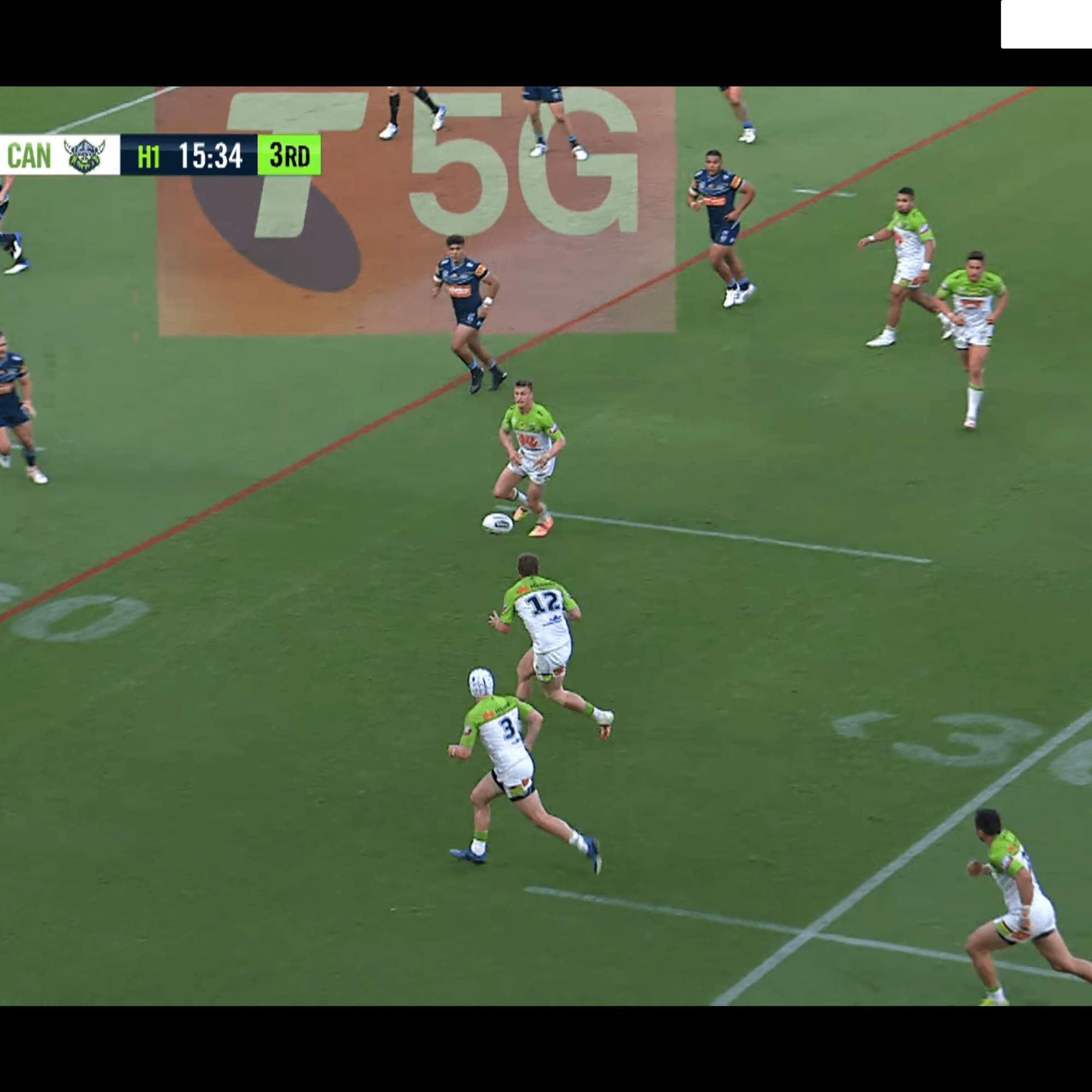

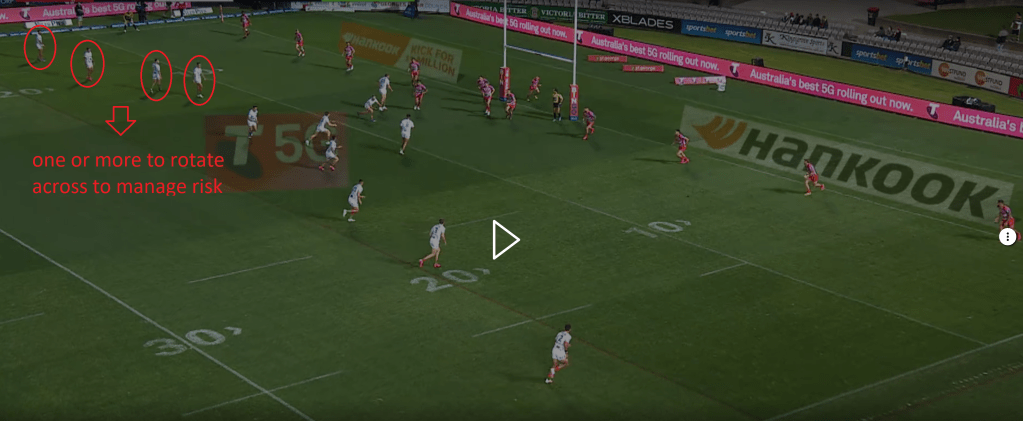

Post the shift from dummy half my suggestion is for a non-attack side player to rotate across in defence as shown in the picture below.

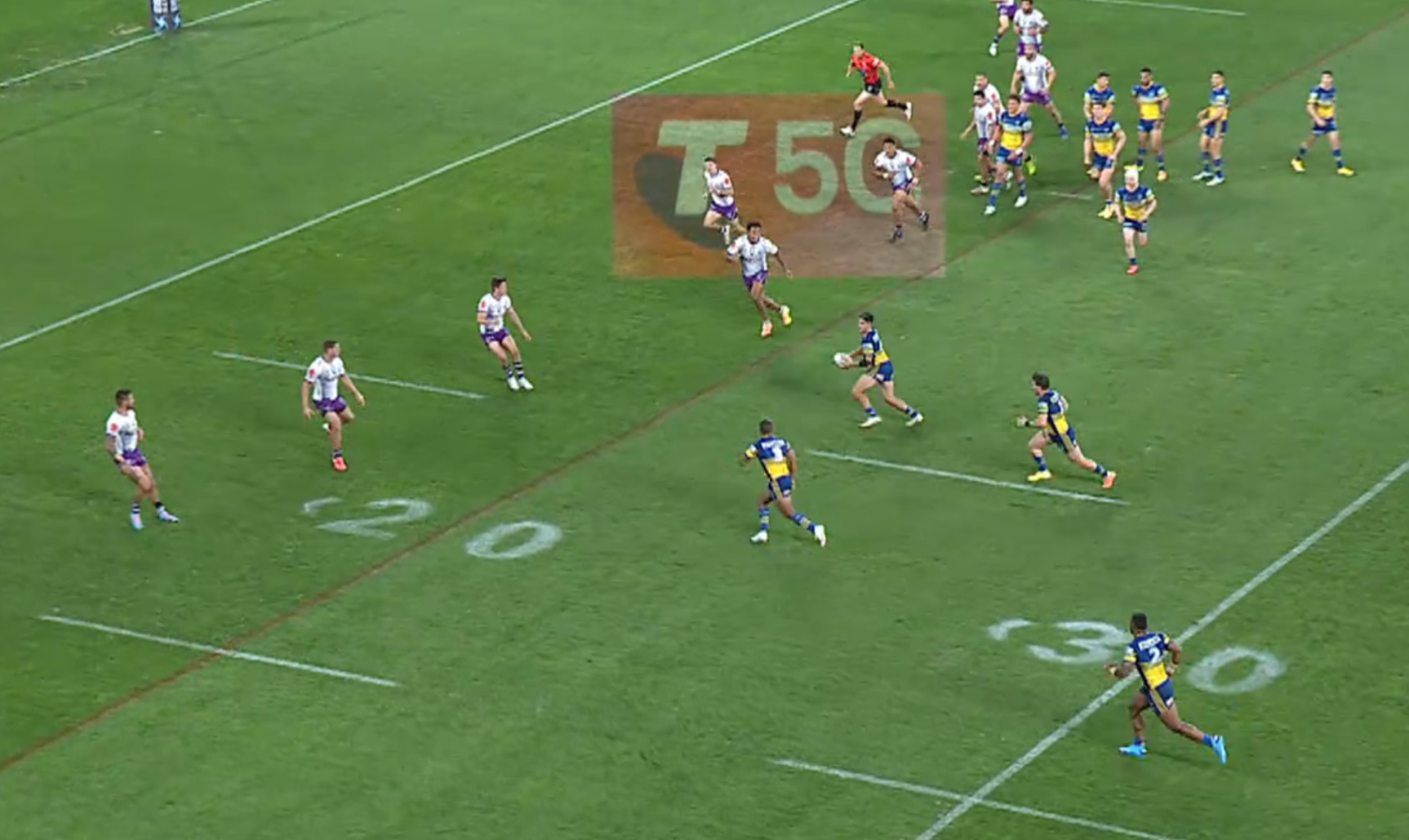

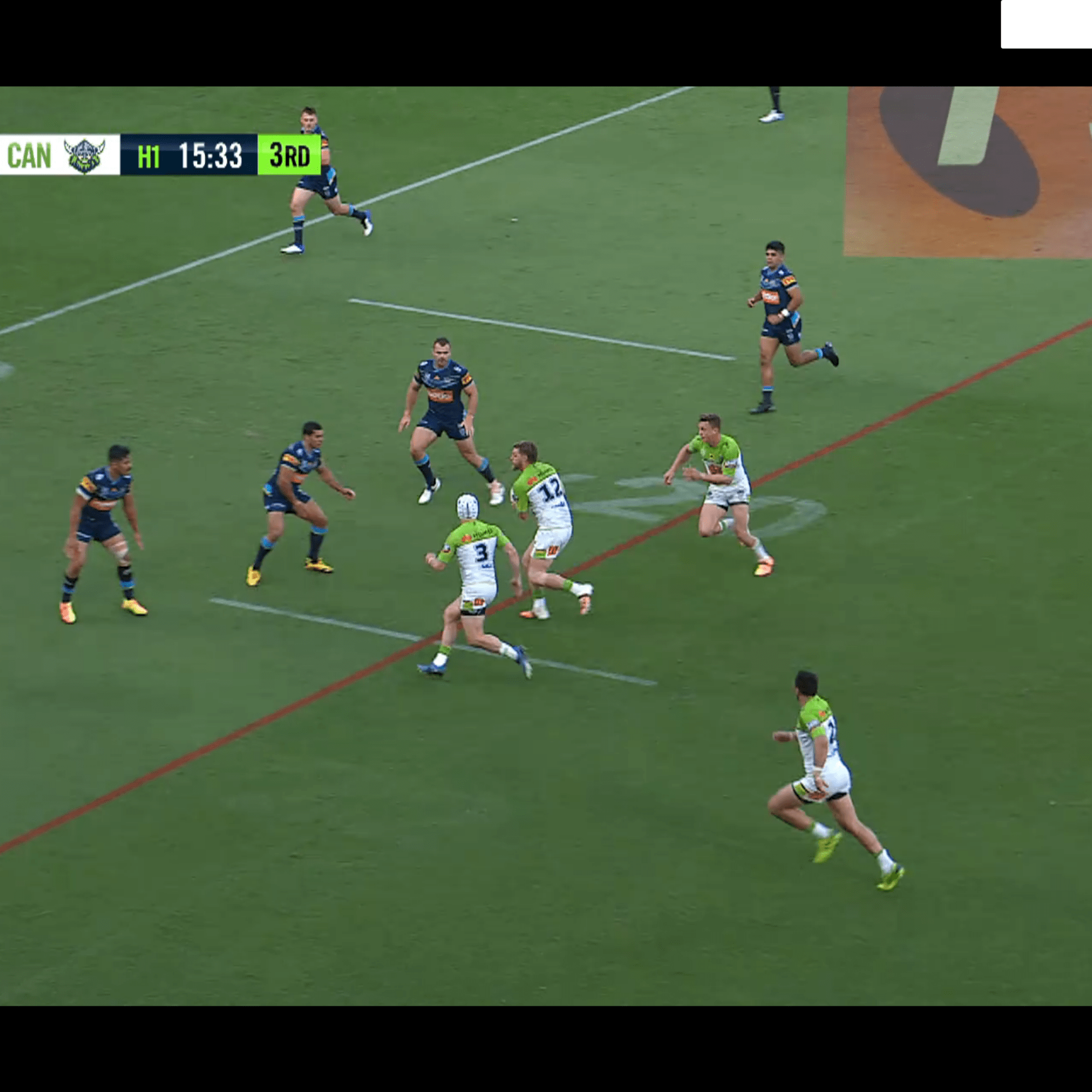

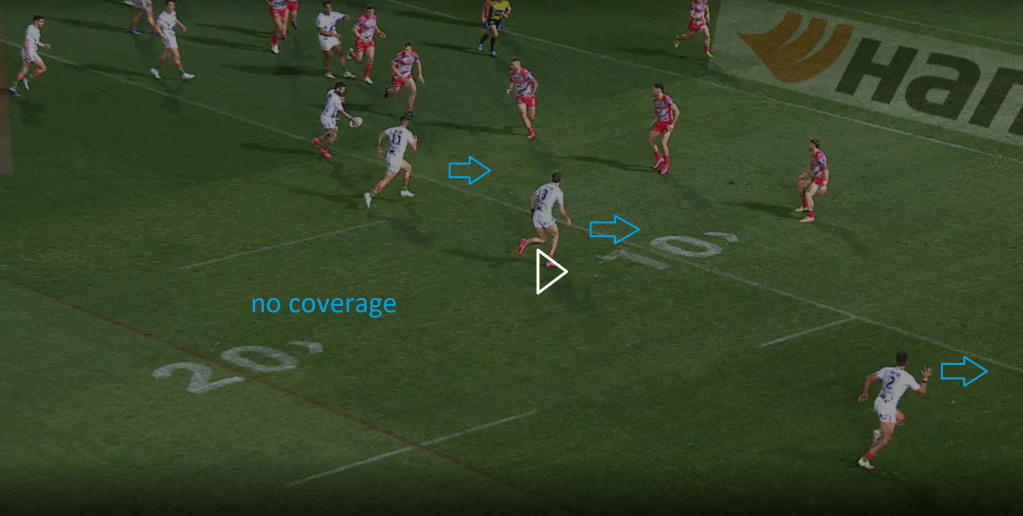

Attacks like this are very common with all attackers committed with no coverage if something goes wrong – ie no risk management.

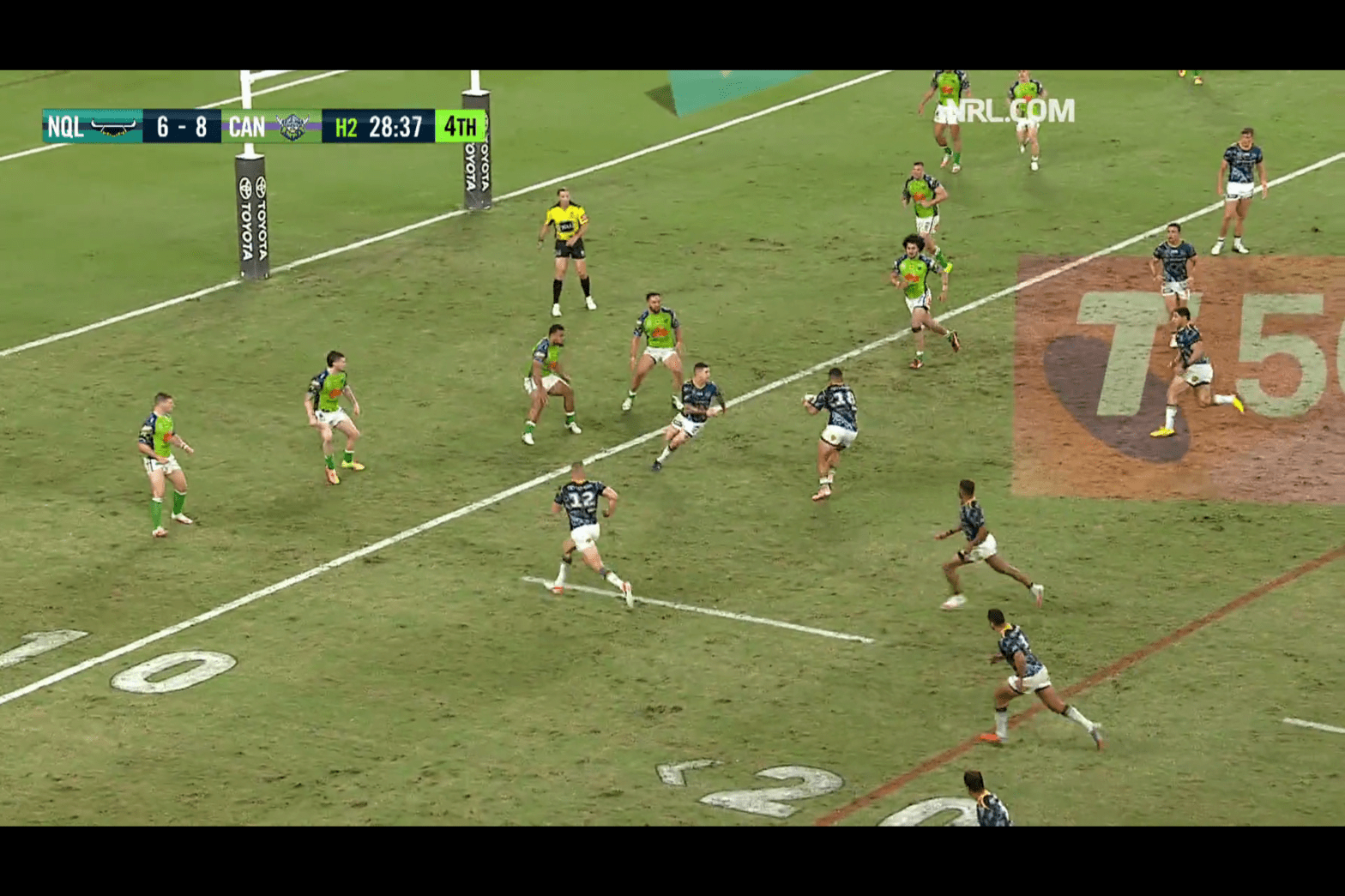

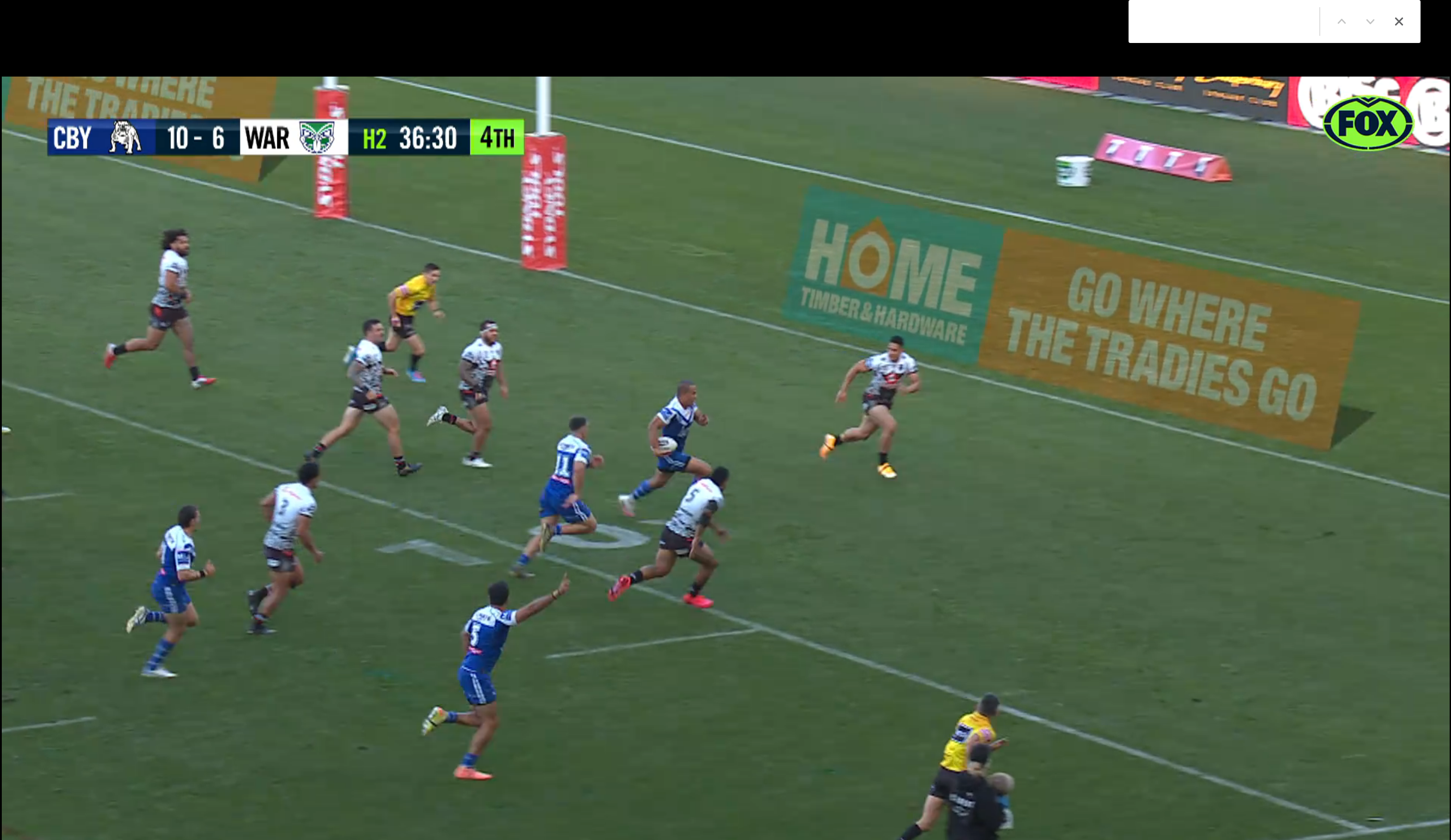

By the time Corey picks up the ball the rotating defender could be close to in front – at least closer and deeper than Cody.

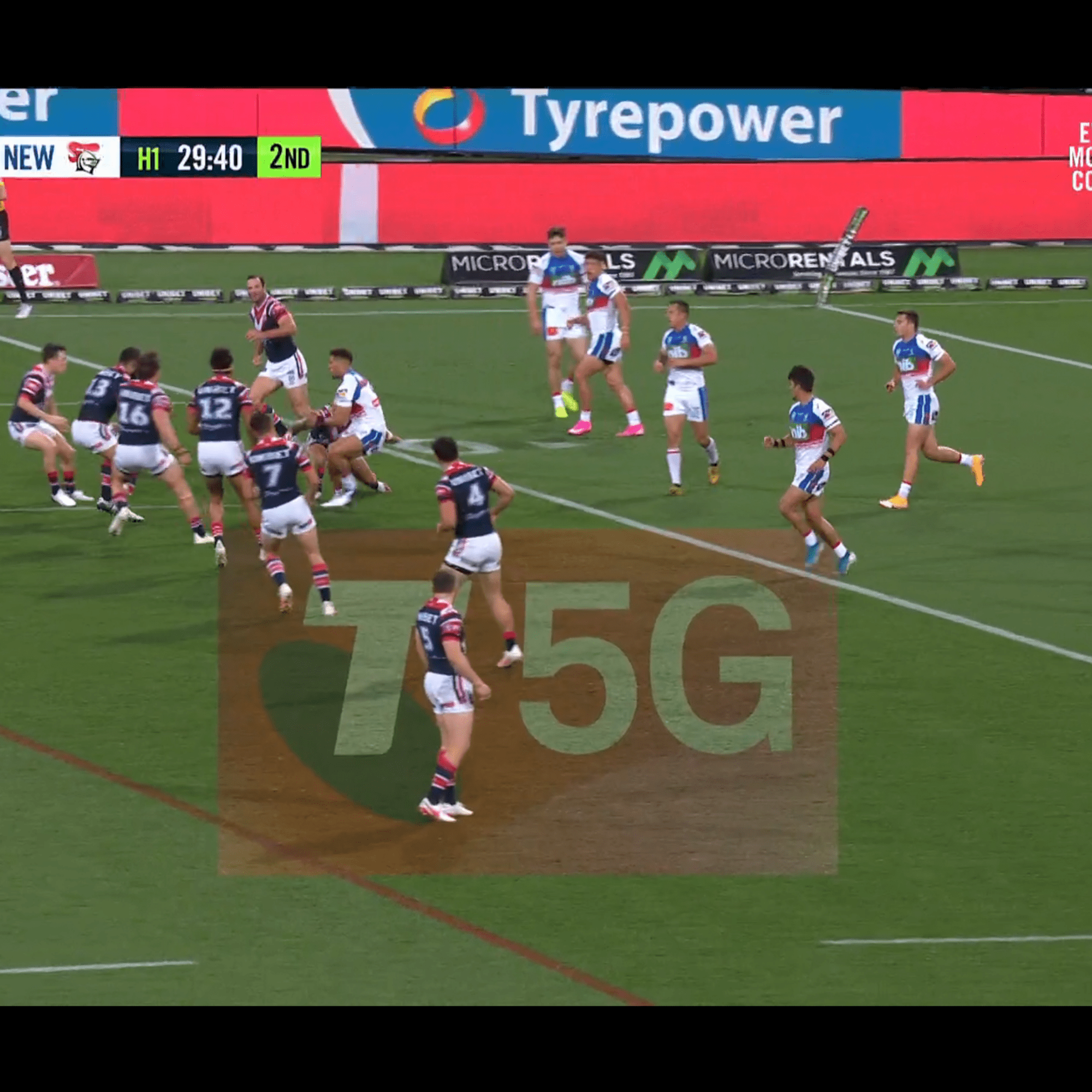

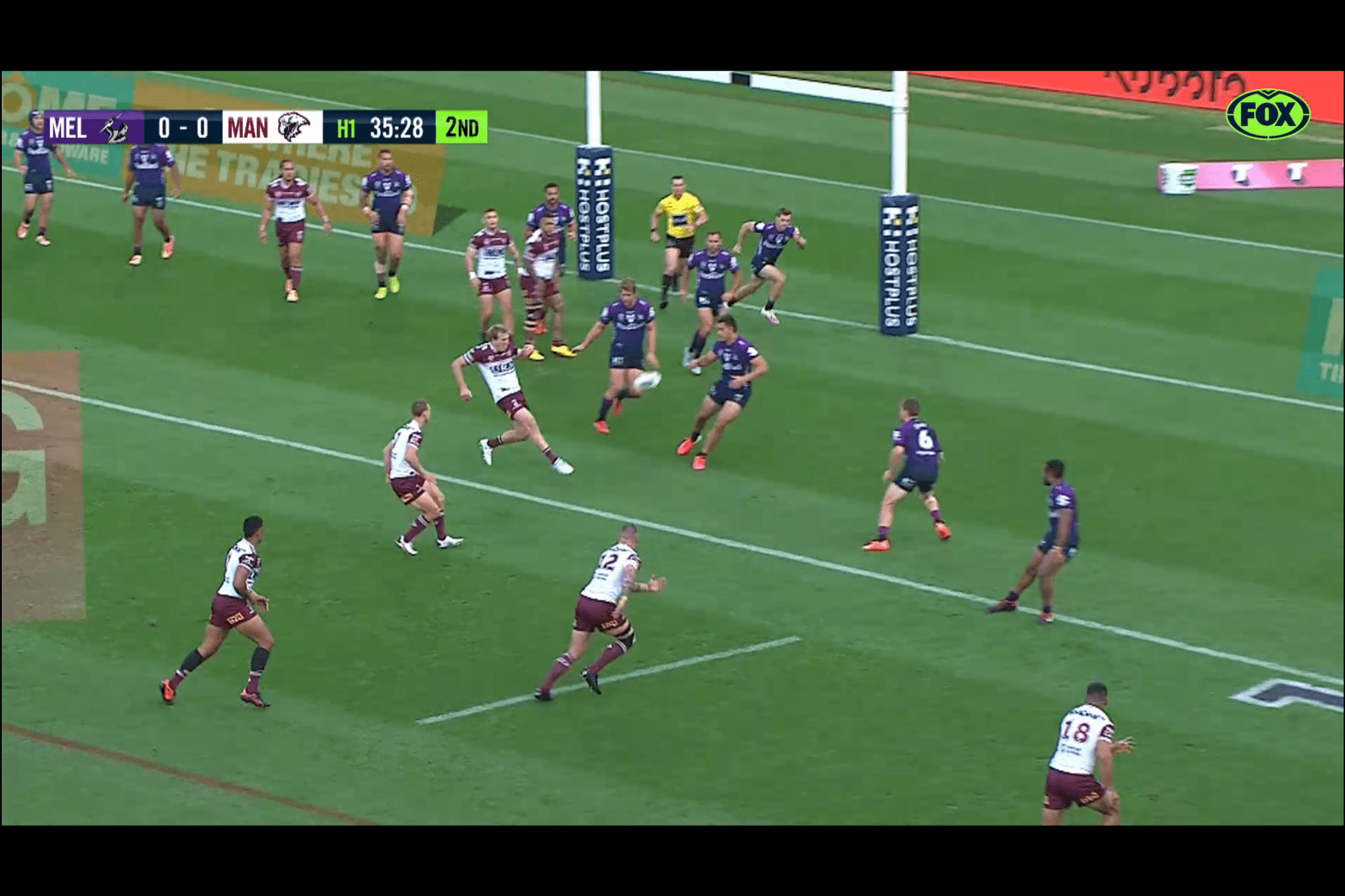

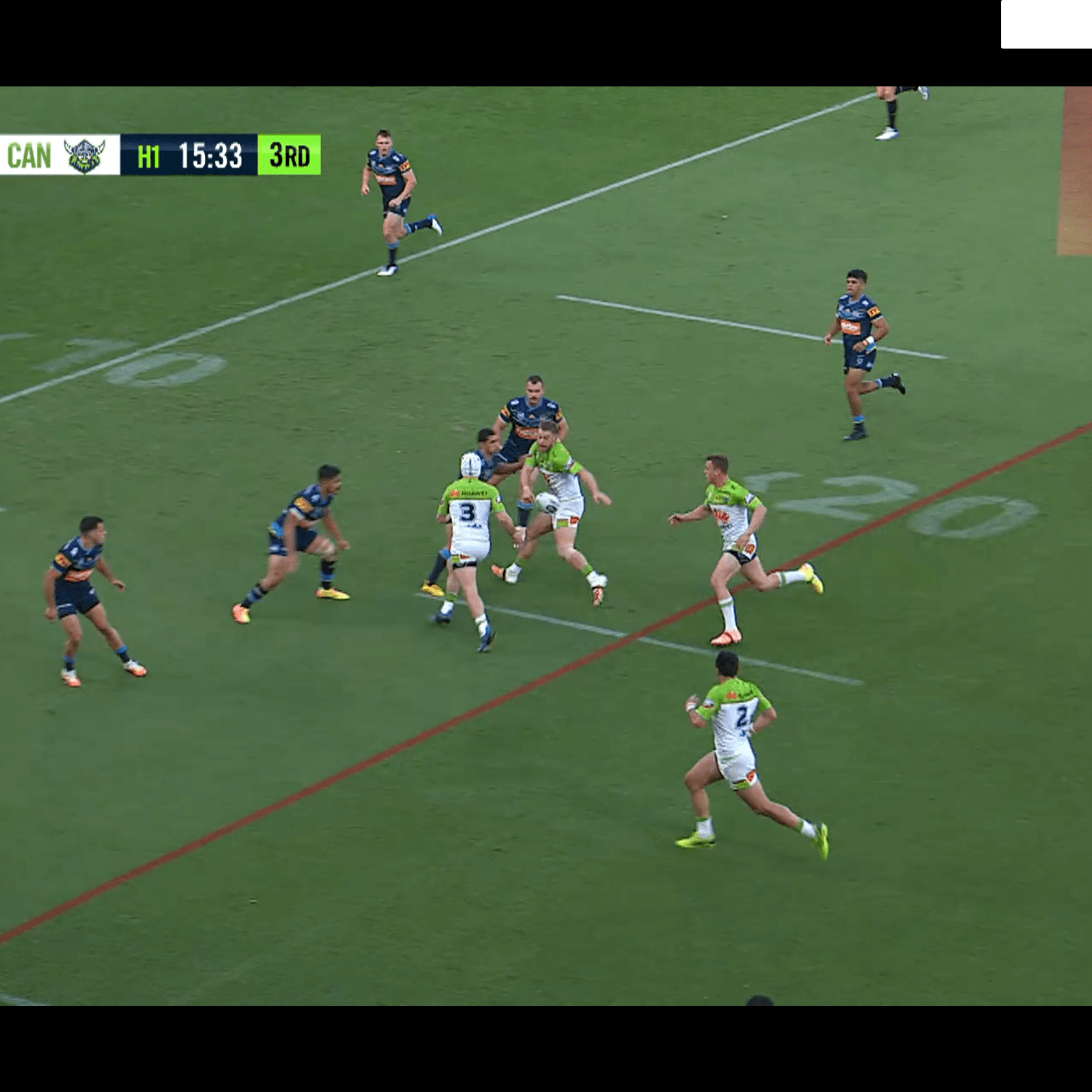

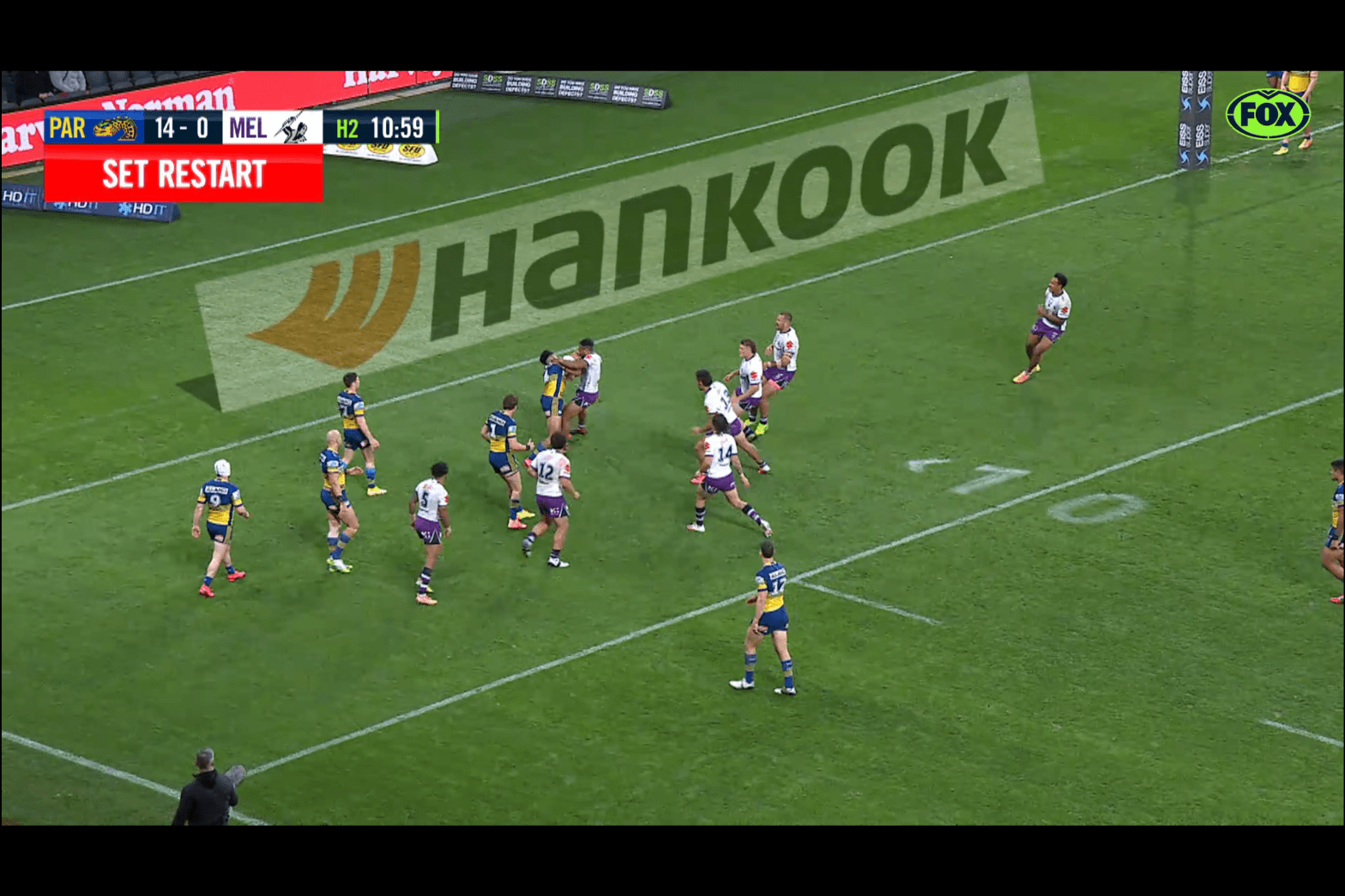

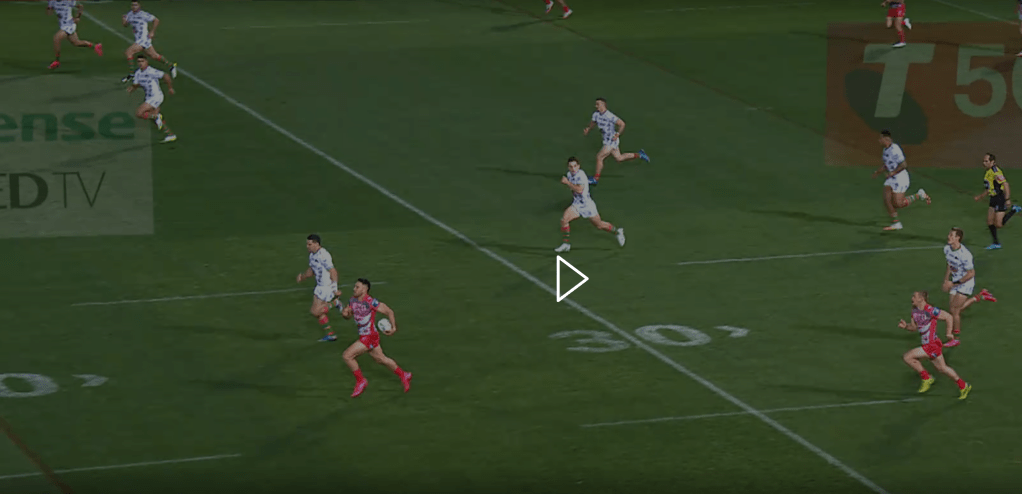

In this last photo South’s fans would be impressed with 8 defenders chasing but it would have been even better if they never had to chase at all. The players I suggested rotating would have had a 20m chase tops – instead they end up chasing for 100m. Even if they had brought him down the defensive line would be shot.

So is the expense of a regular 30m jog for a non-attacking side player into a defensive position worth the prevention of a 12 point swing and the gassing of 8 players? It would put a lot of load on this player especially a playmaker who needs to be on the ball for the next play – maybe the centre/winger could share it?

I’m sure there are other options to cover this risk but the point is no NRL club is deploying any strategy to cover this risk.

Actually Dane Gagai went the length of the field in Origin 1 last year so it is not even being managed at this level.

Is this worth bothering about? I say yes as the cost to manage this risk is extremely cheap – just some practice at training with players understanding their role to cover the “just in case” scenario of attack gone wrong.

It’s more than just intercepts

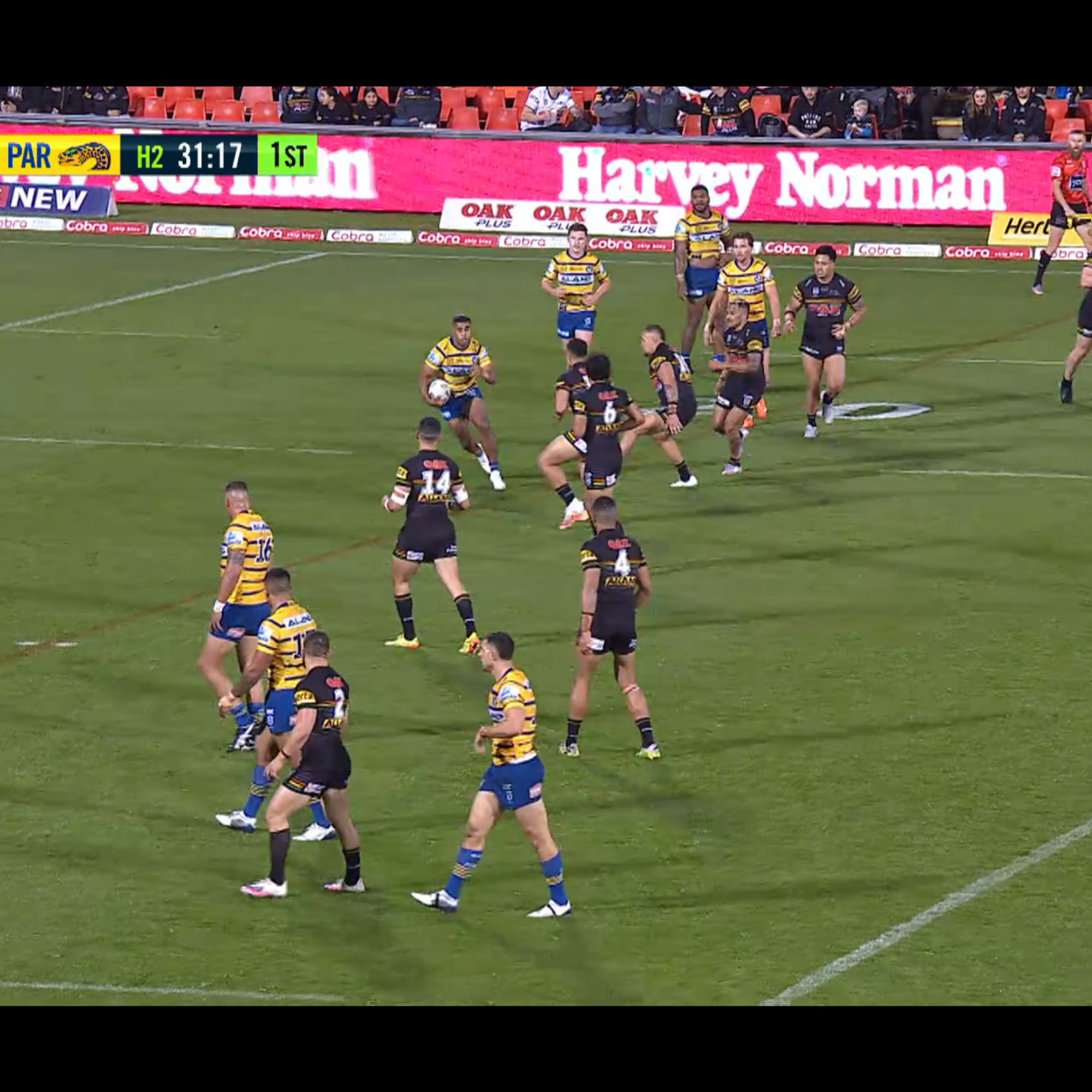

Consider how often the intercept’s close cousin the kick which gets “trapped and scrapped” (as shown above) or just the plain-old fullback/winger picking up an attacking kick and going the length of the field occurs.

Starting to appear as something that should be managed? Fortunately the strategy proposed above covers all scenarios.

I have started a count from round 10 and we will see how many points could have been prevented with this simple risk management exercise (I’m going to assume the cover defender makes the tackle and if not slows them enough to allow other defenders to make it).

Running Tally – 22 tries

| Round | Events | Tries | Comment |

| GF | 1 | 1 | Vunivalu |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | |

| F2 | 1 | 1 | Paulo |

| F1 | 2 | 2 | Williams, Katoa |

| 20 | 1 | 1 | Taylor |

| 19 | 4 | 3 | Spry, Addo-Carr, Valemei, Whitehead |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | Gagai |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | Addo-Carr |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | 3 | 2 | Addo-Carr, Vunivalu, Moses |

| 12 | 4 | 4 | Papenhauzen, Dufty, Johnson x 2 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | Fogarty |

| 10 | 3 | 3 | Katoa, Blake, Addo-Carr |