In this article we will cover bomb defusal which is another area where I feel risk could be better managed in the NRL (previous article: what can Dane Gagai teach us about risk management).

We all know teams with the best defence regularly contest finals matches – so why do I consistently observe poor defence on the last tackle – especially when the bomb goes up? (I’ll cover some offensive strategies to take advantage of this aspect later)

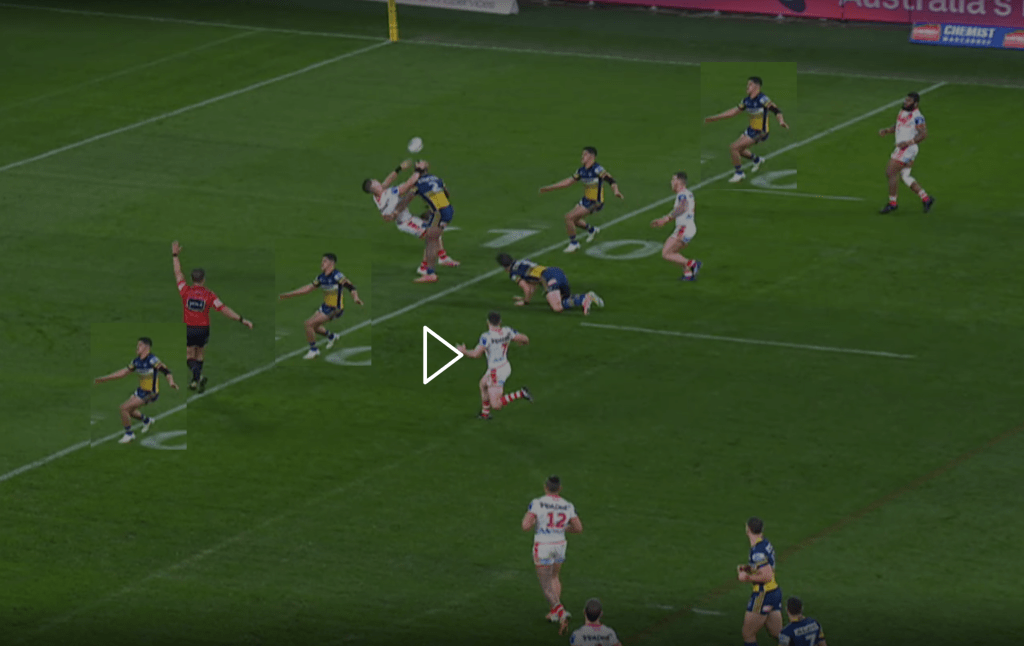

Here is a sequence of images from bombs from the last round of football – have a look at the defensive positioning of players in particular.

The Storm in particular terrorised young Tuipulotu bombing consistently for Vunivalu going close to scoring many times and earning several forced drop-outs.

What I notice from the images above is:

- commitment of too many defensive players to the location of the bomb drop

- lack of commitment of inside defensive players to be involved in the play

- the defensive players who do commit do not position themselves well ‘just in case’ the attacker catches the ball

- no adjustment of defensive strategy depending upon the location of the bomb drop or the strength of the attacker

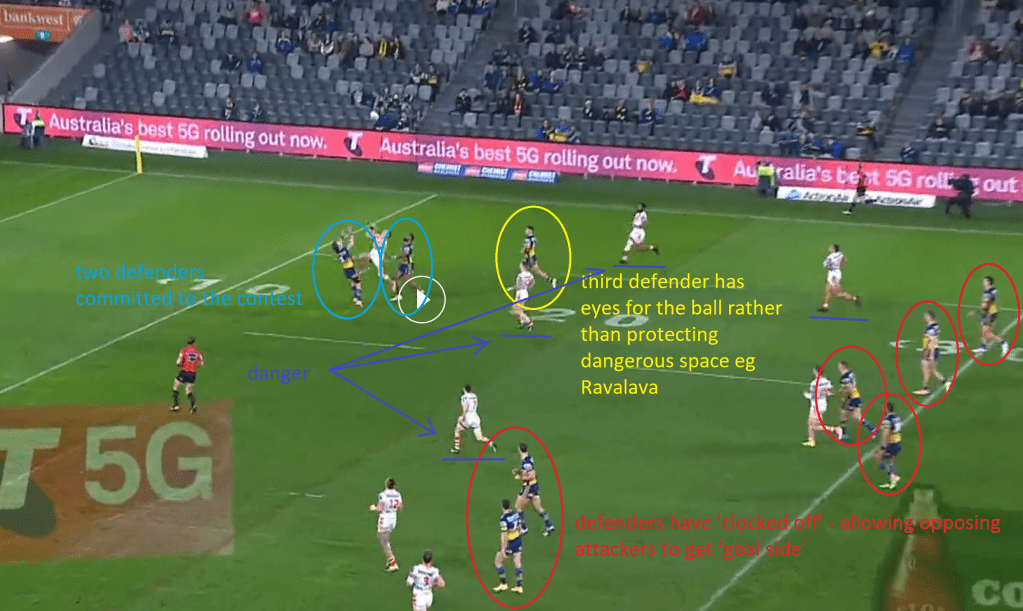

Let’s zero in on one example to walk-through the above factors in detail.

Zac Lomax has proven himself to be a real attacking ‘bomb’ threat scoring and setting up several tries this season. In the example above Sivo has tried to run him off the ball which is a good strategy when done legally.

The key point is however once Lomax has run past him (run-off did not work) Sivo should try to position himself behind the ball to cover attacking players.

Dylan Brown (circled in yellow) also commits to the contest rather than covering dangerously positioned attackers like Ravalava or McInnes. Though to be fair to Dylan the fact there are no other defenders nearby didn’t help.

My theory for defenders switching off is that they are ‘conditioned’ by general field position kicking that there is no need to assist.

With field position kicking the kick is rarely contested by definition (too much ground to cover) so it makes sense to allow the forwards to have a rest. We have all seen forwards taking up to three tackles to get back onside.

Therefore when a bomb goes up I suggest many defensive players switch off – even though in this case the kick will be contested.

I’m a strong believer in cross-pollinating effective strategies from other codes. When a bomb goes up it is very similar to a contested marking situation in Australian Rules and anyone who follows this code would be mortified at allowing so many attacking players get ‘goal side’ of their defenders.

So what can we learn and potentially apply from Australian Rules contested marking situations? Here is some general tactics that should be thought about:

- defenders placed goal side of their attackers

- defenders not in the contest covering attackers in dangerous space

- getting superior numbers to the contest

- use of communication between defenders eg the closest player should let the bomb defuser know if it is going to be an easy catch (not contested) or contested

- spoiling the contest – conceding the opponent is more likely to catch the ball than yourself and punching the ball away to a safer position

- modifying the approach to ‘marking’ vs ‘spoiling’ based on the opponent and field position

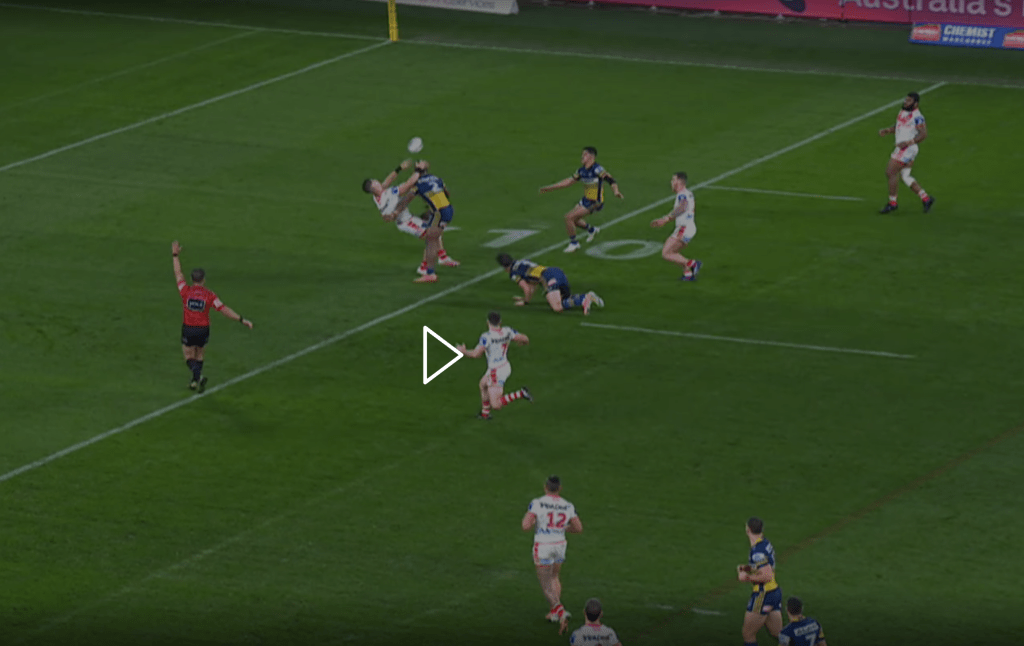

Defenders goal side, covering dangerous space & superior numbers win out

By goal side I mean defenders placing themselves between their own try line and the attacker. By covering dangerous space I mean placing themselves between the location of the contest and the attacking player.

In the example above the assistance of extra defenders would have diminished the risk of Clune, McInnes and Ravalava.

Communication between defenders

This one is hard to observe – impossible from the TV and even if you are at the game you could be far away or crowd noise could wash it out. Because of this the impact of defender communication is understated and not commented on.

As someone who has played both rugby league and australian rules one of the biggest shocks was the amount of communication involved and expected in the latter – seemingly perfectly executed practice drills would be rerun because the coach could not hear ‘voice’. I will leave it to you to decide if the level of communication could improve for defenders in a bomb defusal situation.

To spoil or not?

Under what if any circumstances should a defender consider not trying to catch the ball in rugby league but instead just punch it away?

Well obviously not if the bomb is uncontested but what if you are Jorge Taufua up against Daniel Tupou and the ball is coming down 1 metre from the try line and 1 metre from the sideline (a nightmare scenario for Manly supporters)? What are the range of outcomes?

- Jorge catches the ball

- tackled in field of play

- forced into touch

- forced into in-goal

- Jorge drops the ball backwards

- lands over side line

- lands into in-goal recovered by defender

- lands into in-goal try to attacker

- lands in field of play recovered by defender

- lands in field of play recovered by attacker

- Jorge knocks the ball on

- Tupou catches the ball

- try scored

- held up in-goal

- tackled over sideline

- tackled in field of play

- Tupou knocks ball on

- Tupou drops or taps the ball backwards

- lands over sideline

- recovered by attacker tackled in field of play

- recovered by attacker try scored

- recovered by defender

The above list is not complete but covers the majority of outcomes. Green = successful defusal, Orange = new attacking set, Red = try conceded.

What immediately becomes apparent is that there is not a lot of upside to Jorge attempting to catch the ball – when the ball lands in this location. A bomb that lands in the in-goal substantially improves his outlook for catching. Similarly a bomb that lands 20 metres out and further in field also improves his outlook. It also changes with the threat level of the attacker and the bomb defusal capability of the defender (something else that is catching on from AFL is the ability to catch the ball over your head ie with arms extended rather than catching on your chest).

What if Jorge assessed the risk of catching is too high based on all the factors and instead attempts to punch the ball over the sideline or touch in-goal line? Spoiling is much easier than catching in a contested situation – it would definitely reduce the chances of Tupou catching or tapping the ball back vs Jorge trying to catch it. What if Brad Parker comes across and also tries to spoil?

We seem quite understanding when fullbacks or wingers defuse a grubber by grounding it, running it or tapping it over the dead ball line – so why not for bombs in certain circumstances?

Summary

Whether you agree with ‘spoiling’ or not is beside the point – I’ve included several other potential strategies from another code which spends a lot of time thinking about minimising the risk of aerial contests and I feel they are worth consideration.

The key point is that to manage risk effectively you should assess the risk of the range of outcomes and devise your approach/strategy from there.

very good post, i actually love this web site, carry on it

LikeLike